Adversarial Networks: on Joseph Nechvatal

by Katherine Williams

for Impulse Magazine

December 2025

Information Noise Saturation, Magenta Plains, NYC

In Joseph Nechvatal’s diptych graphite drawings, figures

navigate a world without coordinates. Amidst Mind of the World (1984),

an armored, oversized, machinic assemblage of a

soldier charges toward little but apparition; on the left drawing, partial

outlines of bodies collide with a haphazard array of jagged graphite lines,

concentrated in the ominous, barely visible gaze of a man’s face at the center.

In False Friends (1982), policemen scrutinize a protester and stand firm

amidst pop-cultural figurative sketches. In earlier drawings by Nechvatal, done with graphite on paper, similar figures of

gonzo caricature appear, but the works on display in Information Noise Saturation

at Magenta Plains show a texture of overload obscuring the legibility of

their form.

No Future, 1983 Graphite on paper Diptych, Overall 11 x 28 in

Nechvatal’s compositions approach something like

narrative, however fragmented and mercurial, filled with characters who would

be right at home in noir and detective fiction were they not thrown into the

information landscape of the 1980s. The drawings depict a terrain not quite a

cyberspace (a term coined amidst the years during which the works were made),

in which axes appear as simulacra, but an imaginary geography without

landmarks, where figures emerge in associative disunion. That absence of

landscape is a lack endemic to Nechvatal’s post-A

Thousand Plateaus world—writing in Artforum

in 1984, Kate Linker noted that postmodernism’s “empty discourse of

surfaces” leads to the “erosion of all coordinates of value,” a haphazard

disintegration in which individuals are left to decode the irrational

simultaneity of a greyscale information space.[1] In Nechvatal’s approach, the consequences of such erosion are

best expressed as a density. Skeptical of pop art, whose absorption of mass

media Nechvatal might consider unequipped to address

consumer fetish, he once described it as “art

noise,” which “counters the effects of our age of simplification.” Noise

is an appropriate pictorial language to accommodate the proliferation of

information technology, visual media, and financialized markets that

characterized the 1980s—but it’s the delicacy of Nechvatal’s

marks, however condensed they may become in whole, that best suggests a more

nuanced sentience to the scene.

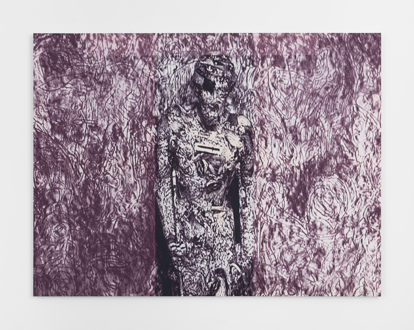

The

three larger-scale works in the exhibition, made a few years after the

graphite drawings, attend to Nechvatal’s “Informed

Man” character, who lends their moniker to his Profusely Informed Personage (1986).

A statue of Babalú-Ayé, a popular orisha

in Santería worship, is covered in and set against a

background of scans of figures taken from popular magazines, layered with

drawing by Nechvatal. His photograph of this scene

was then taken up by an imaging service for billboard production, which

airbrushed the digital image onto canvas. In this process, Nechvatal’s

work invokes a similitude to other considerations of the automatic: Wade Guyton’s

inkjet prints, with the wrinkled imprints of a machine’s errors and will, or

the fuzzy outputs of Matthias Groebel’s

airbrush painting machine. The spray method is attractive in that it joined

(and predated others in) a long genealogy of artists using automation to

consider the withdrawal of the painter’s hand over the past half-century. Here,

though, that withdrawal is interesting only to the extent that it bears on the

character—that the informed man is being subjected to yet another step of image

production, blurring the distinction between the fictional world in which he

resides and the real method of his construction.

Profusely Informed Personage, 1986 Computer-robotic assisted acrylic painting on

canvas 72 x 96 in

Between

1997 and 2002, Jack

Pierson utilized a similar acrylic spray technique for billboards in

a series of works; both foreground the printing marks and pixelation,

which render the scene mediated, but Pierson’s images are airy and dislocated,

while Nechvatal’s works with his Informed Man dip

into a register of violence. The figure is a carcass, the rot of which is

conveyed in the accumulation of detritus upon its form. What is he covered in?

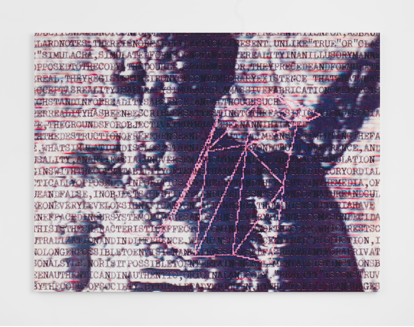

The same image of the Santería statue constitutes Infinite

Apocalyptic Messenger (1987), focalized to the scale of his head and

shoulders. Layered atop the strained figure in an all-caps, imprinted

typewriter font is text from the aforementioned Artforum

essay on simulacra, and certain phrases stand out: “grounds for objective truth

have been annihilated,” “no longer possible,” “authentic and inauthentic,”

“massive fabrication.” The essay reads Baudrillard

and Debord, examining the loss of indexicality

and reference—that “erosion of all coordinates”—as third-order simulacra

settled in at the dusk of the twentieth century. If theorists of the hyperreal

tended to focus on glossy surfaces, spectacular effects, and shining

ahistorical artifice, though, Nechvatal’s informed

personage, weighed down by such mediatization, shares

less in common with the Disneyland phenomena of simulacra that captivated Baudrillard and Umberto Eco.

The

figure is not so much a model of excess’s gleaning emptiness than of the

density of the zombified form which it saturates:

certainly, the anguish in his hunched shoulders, in the burden of information

he carries without say, is a kind of body horror. One thinks of N. Katherine Hayles’s observation that posthumanism

erases the distinction “between the biological organism and the informational

circuits in which it is enmeshed,” and of the height of cyberpunk, concurrent

with Nechvatal’s work, seeking to represent the

disfiguration and contamination endemic to early onset information society.[2]

The body of the 1980s, absorbing electromagnetic waves and nuclear radiation,

was antimaterialist and permeable—Nechvatal’s

figure is a useful character, then, for recalling a kind of somatic fatigue. In

this, the Informed Man is a more neo-expressionist cousin to something like Ed Paschke’s

televisual figure in Nervosa (1980): a body as seen through an

interface, through a strange grid of uncanny exposure in the early days of

screen glow, moire distortions, raster lines, and

channel surfing. However attractive the rhizomatic

epistemology of poststructuralism may be, here the physical consequences are

given their due.

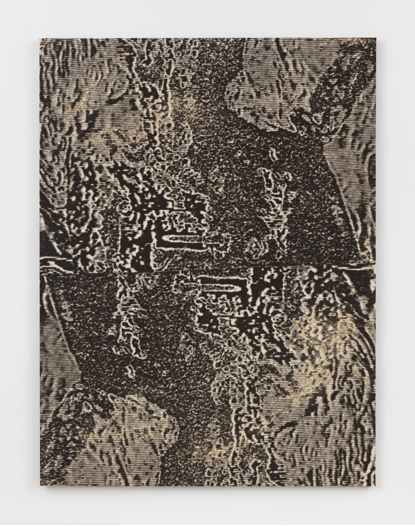

A

later work, Without Chains (1990), is a somewhat abstracted composition

of the Informed Man as Narcissus, gazing upon his unfocused reflection—a

darkened greyscale tone, similar to topography from a distance, renders him

almost unrecognizable. There’s certainly humor in the reflection now, being

that of an actual statue, not merely a seductive likeness to marble. If it

functions as an intimation of the frayed postmodern subject with no exalted

Renaissance self left to lose to idolatry, it insists

equally on the possibility of a profusely informed self-recognition. The scene

is reflected along a line which runs across the middle of the canvas, an

imprint of Nechvatal’s hand in the printing process:

intentional or not, it underscores the politics running against the ostensibly

totalizing force of visual noise. (Without Chains was made the same year

the Gulf War began, which was described by Frances Dyson as a conflict in which

the consequences of action were seen through “the snow of signal termination.”)

Together, the three depictions of the Informed Man are a starkly hopeful

narrative triptych, as though his persona may be wrenched back into the

register of affect, once said to have been traded for surface in postmodernism.

It becomes a gambit that the suggestion of subjectivity, however warped behind

an interface that seeks to level it, remains alive somewhere in this deterritorialized plane.

Without Chains, 1990 Computer-robotic assisted acrylic painting on

canvas 96 x 72 in

The

informed man looks quite a bit like Charles Csuri’s Sine Curve Man (1967), an early

figurative computer drawing completed by an IBM 7094. Thin, clean lines

constitute Csuri’s drawing, which was completed with

a drum plotter, and are prescient more so of a treachery undergirding

technocratic efficiency. But both faces collapse and sink, rendered grotesque

by the necessity of information technology in their construction. The disfigurative portrait seems to remain an ever-attractive

strategy of picturing the subject in the territory of his age. For Nechvatal, this might be the seeds of a scattered and

profuse information society, in which a dense and disheveled horror of

figuration defends the status of the subject. At a time in the mid-80s when

computer graphics were leaning towards metallic seductions and a rudimentary

palette (popularized on MacPaint and Paintbrush for

Windows), it’s an assertion that living with transmission and mediation is not

about surfaces but about obfuscated depths. As contemporary artists like

Phillip Schmitt foreground the opaque, disembodied character of machine

learning, one finds an ambivalent relief in figuration.

There

is an initial longevity to the Informed Man series, with its intimations of

screen media and boundary-melting emulsion of body and technology. It’s a

consideration taken up with device after device, up through works like Tishan Hsu’s distorted topographical compositions over the

past few years. A body embedded in information, native to representational

strategies of the 1980s, is still a compelling landmark.

But

if the raw material of noise was once central to the task of visualizing (and,

it’s implied, evaluating) information’s excess, its status is more volatile

than it was in the age of radio waves and television. It is less the “stuff”

that penetrates and degrades the human body living amidst nuclear proliferation

than that which constitutes the image itself: the addition and removal of

noise—forward and reverse diffusion—furnishes the training process for

generative models, which learn to make images by finding forms in randomness.

The idea, as it was put in early papers on these models, is to destroy

structure in data, such that it is possible to put it back together again.

Infinite Apocalyptic Messenger, 1987 Computer-robotic assisted acrylic painting on

canvas 72 x 96 in

Nechvatal’s triptych is useful, then, in thinking

about what kind of form might be constituted in such a violent array of

randomness. But it’s curious that this series on the Informed Man, ostensibly

apropos in their attendance to the deteriorative effects of immersion in screen

media, ends up yielding to the more reticent fury of Nechtaval’s

graphite drawings. The uneven lines and variable shades invite viewers to see

noise itself as a process of mark-making. Before classical empiricism defined

information as the external “stuff” of experience, it meant a conferral of

form, a process of shaping—one suspects the drawings get closer to that

significance. The Informed Man may be likened to a figure made in noise’s timestepped removal of perceptual features, but the

alternative allure of the drawings lies precisely in their method, not so much

about reproduction as about entropy. In foregrounding form over affect, they

are slyly tenable.

There

is an irony here, a strange inversion: the hand involved in the diffusion

happening in these drawings is now a recursive algorithm, while the automated

method invoked in the acrylic work feels based in a visual culture both

valuable and overfamiliar. All of Nechvatal’s work

contains a classic tension between the profuse disorder of experience and the

forms that order that chaos. It is the potential of the drawings, though, that

most stands out: in thinking not only about how noise may confer and obscure

form, but how both noise and form are manipulable—spun

and undone, added and removed, legible and then not. Graphite may no longer be

a paradigmatic tool by which that process occurs, but the artificial forms that

constitute new images find a curious ancestry in that lineage.

Joseph Nechvatal: Information Noise

Saturation, Magenta Plains, 149 Canal Street, NYC, November 6 through

December 20, 2025.